Gully Foyle is my name / And Terra is my nation. / Deep space is my dwelling place / And death's my destination.

Gully Foyle is my name / And Terra is my nation. / Deep space is my dwelling place / And death's my destination.On one level, The Stars My Destination (originally published in the USA as Tiger! Tiger!) is an exercise in vengeful monomania. The novel begins with the antiheroic protagonist Gulliver Foyle, Mechanic's Mate 3rd Class ('Education: None; Skills: None; Merits: None; Recommendations: None' (p. 16)) enduring his 170th day in a pressurised tool cupboard, scuttling around the remains of the Nomad, the wrecked, depressurised freighter he was a crew member of, in a patched space suit searching for oxygen and supplies. When the Vorga, a sister ship to the Nomad also belonging to the Presteign clan, discovers but fails to rescue him, the naked rage engendered within Foyle drives him to pursue its crew and enact his revenge. A series of thrilling set pieces follow, that are made just about credible by the verve of Bester's prose: Foyle's reanimation of the Nomad, his escape from the Sargasso Asteroid, and his break out from the Gouffre Martel prison are all highly dramatic. During the course of events, however, Foyle finds himself at the centre of a struggle between the colonists of the Outer Systems and the remaining inhabitants of the Inner Planets, both striving to discover a cache of PyrE, a 'thermonuclear explosive... detonated by thought alone' (p. 248), to assist them in their struggle.

In the midst of this page-turning narrative, as well as unsettling the reader by constructing a homage to the experimental novels of the eighteenth century by means of a sequence of typographical flourishes (p. 233-243), Bester somehow finds time to coin a number of the staple tropes of contemporary SF. Anyone familiar with Iain M. Bank's Culture will recognise the genesis of 'glanding' in the adaptation of Sheffield's salivary glands, 'prepared to respond with an anaphylaxis secretion' (p. 222). Foyle's 'rewiring' with 'microscopic transistors and transformers... buried in muscle and bone' making him 'more machine than man' (p. 128) predates William Gibson's cyberpunk reworking of similar ideas by some 30 years. Furthermore, Bester's description of the abilities Foyle gains as a consequence of his transformation have found their expression in media other than the printed word: it is impossible, for example, not to envision those scenes within which he activates the acceleration 'of every sense and response in his body... by a factor of five' (p. 130), effectively slowing down the world around him, in anything other than Matrix-style 'bullet time'. In addition, we are introduced to a clutch of other ideas, such as 'jaunting' (teleporation by means of will alone), Disease Collectors (p. 153), and Sympathetic Blocks (p. 155), to name but three.

There is nothing to like about 'the walking cancer... Gully Foyle' (p. 103), who has 'robbery and rape', 'blackmail and murder', and 'treason and genocide' (p. 220) to his name. For the first three quarters of the work, Foyle is largely 'Cro-Magnon' (p. 65): 'Run. Fight. Punch. That's all you know. Beat. Break. Blast. Destroy' (p. 86). The tiger-stripe tatoos emblazoned across his head by the inhabitants of the Sargasso Asteroid during his initiation suit the cast of his personality, even more so when he attempts to have them removed only to discover that they reppear when he loses control of his temper. However, just as Blake's god created the tiger as well as the lamb, so Bester, rather than afford the protagonist redemption in the final quarter of the book, chooses instead to recast Foyle as an Everyman figure in an attempt to coerce the reader into associating with him.

There is nothing to like about 'the walking cancer... Gully Foyle' (p. 103), who has 'robbery and rape', 'blackmail and murder', and 'treason and genocide' (p. 220) to his name. For the first three quarters of the work, Foyle is largely 'Cro-Magnon' (p. 65): 'Run. Fight. Punch. That's all you know. Beat. Break. Blast. Destroy' (p. 86). The tiger-stripe tatoos emblazoned across his head by the inhabitants of the Sargasso Asteroid during his initiation suit the cast of his personality, even more so when he attempts to have them removed only to discover that they reppear when he loses control of his temper. However, just as Blake's god created the tiger as well as the lamb, so Bester, rather than afford the protagonist redemption in the final quarter of the book, chooses instead to recast Foyle as an Everyman figure in an attempt to coerce the reader into associating with him.Cheated of his revenge, Foyle is made to acknowledge that 'revenge is for dreams... never for reality' (p. 194), and that his autodidactic quest to 'turn [himself] into a thinking creature' (p. 212) has been futile: 'we prattle about free will, but we're nothing but response... mechanical reaction in prescribed grooves' (p. 247). Whilst Foyle may crave punishment and purgation, 'to pay for what [he has] done, and settle the account', he is forcefully reminded that 'there's no escape' (p. 249) from oneself. In a dense series of symbolic exchanges with a malfunctioning bartender robot that appears to manifest an epiphany of independent thought before it expires, we are exhorted with Foyle to accept that life's challenges must be confronted 'because you're alive. You might as well ask: Why is life? Don't ask about it. Live it... Don't ask the world to stop moving because you have doubts... Life is a freak. That's its hope and glory' (p. 251). This exchange leads Foyle to undertake a final wild quest that he hopes will let the world make its own decisions: 'we're all in this together. Let's live together or die together... I make you great. I give you the stars' (p. 255).

On a personal note, this volume is the one that ingnited my interest in the SF Masterworks series. It in every way merits its reputation as a Golden Age classic, and I found it a wonderfully satisfying read, better than any film or TV series. I sincerely hope that it is never filmed. Mind you, I said that about I Am Legend too, and look what happened...

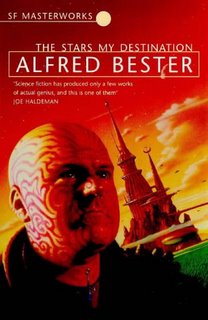

Note: The Stars My Destination was the fourth entry in the 2001 hardback SF Masterworks series (first cover image above), and the fifth entry in the numbered SF Masterworks series (second cover image above). The same cover image was used for both editions, but the former features a quote from Samuel R. Delany, whilst the displays a quotation from Joe Haldeman.